And an Ode to Ambiguous Hollywood Endings

After a certain term of office you can expect that a credible film director will build some savings in the cache of patience with viewers. In fact, certain filmmakers seem to relish in the idea they have an audience “built in” to their productions and can just rely on caustic waves to emerge in response to their latest release. This likely appears more evident in Television when week after week a standard deviation of viewers arrives to share time with their favorite characters. But make no mistake—the same phenomenon exists in film audiences as well. This weird entity manifests itself even more evidently in these technophile times than ever. With the rise of the internet and its wide assortment of software brethren, like personal blogs (Hello!) and social networks, a cult following emerges more vocal than it has ever existed. In the eighties and nineties there were zines and tabloids, before that, perhaps film groups and record parties, more recently the said media has migrated to the web even as some of those old cliques have been partially reborn in the organic world.

But there is perhaps no better contemporary example of the said techno-fan (or maybe cult) phenomenon towards a certain creative celebrity than the one surrounding director Christopher Nolan, whose ambitious and deep tenure—while at the same time a bit short—has garnered a raucous circle between web patronage/criticism and more traditional media such as newspapers and magazines. The major trajectory of his career, launched upon the release of the indie darling Memento, has progressively inspired a robust if not a bit strange following who seem to anticipate his every release with advanced (and perhaps preemptive) applause. Just look at the controversy they started following, or perhaps preceding, the release of Inception, which could only be deduced as a response and reaction to the Oscar snub of the postmodern comic-film The Dark Knight. In large part, these patrons were so outspoken about any critic ‘defiling’ the composition of the Metacritic or Tomatometer with a less than par review the film almost played sidekick (I know, bad.) to the argument itself; albeit briefly. But why is that exactly?

Critics were equally appalled in their new found enemies’ demand to keep the math pure and even wrote counter-articles defending their colleagues’ opinions—even when they disagreed—and positioning themselves to hold whatever view they saw fit in their experience. After all, they did study film, right? Hmm. Well, I don’t know, actually. Anyhow, the controversy is the point to all this and what an interesting if ephemeral, and somewhat trivial, one to occur. All the more I feel a need to involve myself and have a say in it. Because who would really want anything to do with Climategate or Health Care, right? Oh, those are old issues. How bout' oil spills, Bunga Bunga, and America cheating on Britain with France? Still no good? Well, I don't know, there's been way too much coverage of the-u-know-who-wedding. So let's move on.

I submit that this somewhat bizarre anger from Nolan’s fans has something to do with his almost exclusive oblique territory in theme and his often mysterious persona itself. The exhibits include: his ceasing employment of director’s commentary (Though this should not be an obligation.), his ambiguous feedback and commentary and his seemingly unsolvable enigmas that stand in for plots within his films (Surprising the Riddler is not on his list of villains. Blah. I'll stop now.) and more than anything his seriously vague interviews regarding the mysteries he posits. But ultimately, really, does he not at least make intriguing movies? Even if they aren’t Oscar worthy, 10.0, that great in critics’ minds, or even completely understandable, they do seem almost wholly original and at least enthralling. I cannot think of one of his films I was not at least captivated by and had to sit through the entire story just to see the climatic resolution: or lack of. And he does truly serve an ending—much in light to the Greek tradition—grand and intense if not indecipherable at times (i.e. Memento, Dark Knight), but these indistinct outcomes (Is that a misnomer?) are likely what everyone wants anyway: whether they know it or not, the mystery is the candy.

That said, however, I would still have to agree to a certain margin with some critics from the other side of the spectrum that his often enigmatic and grandiose themes (Distributed to everyone but targeted to whom, exactly?) can come off as pretentious and even awkward sometimes. Just thinking about all the dialogue devoted to the nature of justice and integrity in The Dark Knight makes me feel somewhat annoyed and patronized. If you really think about it, is an epic comic movie—meant for entertaining the widest audience mass possible—really the place you lay down all these heavy themes about anomie, indifference, corruption and love? Well, yes and no, I suppose. As an artist you will perhaps never have a better stage to argue your position on all of your heart’s desires and opinions than a major studio blockbuster, but in counter balance to that opportunity is the fact your artistic piece also exists as entertainment and a product of corporate media; meaning the audience and producers have a vested interest as well, and they do not always enjoy the filmmaker presenting ideas as if he/she were instead a professor waxing existential on his stone. And it certainly feels that way sometimes with Mr. Nolan, does it not? Just look at some of the language and subject in his films—not exactly your modern colloquial fare. In The Dark Knight it was philosophy, semantics, Memento, retribution and psychology, and Inception the dialogue ventures towards Science Fiction technobabble, i.e. jargon (Didn't expect that one.).

But all that pulp rind for media consumption brings me to another point. Mr. Nolan is not really new in his endeavors traveling the strange and arbitrary, especially in climax, resolution and epilogue. In fact, that method is old as narrative itself, which, I might say is a lot older than film. But, for the sake of sanity, I will submit to you only a few exhibits in the brief and rich history of motion picture (Sound like someone you know?) where eerie and mysterious finales are quite simpatico with introductions and buildups. Not only are they eerily similar to the coup de grace in Mr. Nolan’s last opus—he admittedly is a well versed student of film history—but they likely informed his latest epic.

Because this piece deals almost exclusively with endings, I think you should know, a lot of spoils follow you if you have not seen these productions. So you might want to watch these films—if you have not already—before reading further. This is not so much a review as it is a dissolving of some very opaque clues which include, in no reasonable order, The Big Sleep, Pan’s Labyrinth, La Jetée, Dante’s Inferno, The Sopranos, Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Taxi Driver, Solaris and Young at Heart, to name a few. Consider yourself warned.

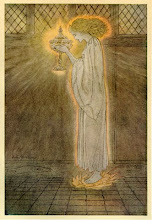

Well, first off, take for instance Inferno—and I know I reference a written work so I must start out with a bit of argumentative dissonance—by Dante Alighieri. Consider the terrain of said poet as he traverses the depths of hell, or what he refers to as Purgatorio, manifested by a spiraling mountain: you might see where I am going. The first layer, Limbo, is not unlike the dwelling of Dom and Mal (Leonardo DiCaprio and Marion Cotillard, respectively, of course.) in their nostalgic fortress of solitude. Indeed the poet’s level is based on the Greco-Roman after-world of Elysium, which was supposed to be a fertile land laden with tall green grass (Famously depicted in The Gladiator, although with more wheat-like stalk.) where dwellers lived out eternity much like in life but with infinite serenity. A place which was eventually referenced ironically as the location of eternal limbo by Christian thought (Inferno especially), because its inhabitants were forever segregate from the exquisite light of rapture; a plane which unfortunately is indecipherable to most common folk despite being depicted so exhaustively in Medieval and Renaissance fresco and iconography.

In the Inferno, Limbo is not meant to be unpleasant at all—instead it is a place of peace not much different than Elysium. The problem is it never changes—it will always be rolling green fields and murmuring rivers, although probably to a lesser exquisite degree than the Greeks or Romans intended. The dwellers of this layer are not even evil people, not even necessarily rampant sinners, they are actually humans who mainly lived outside the sphere of Christendom or simply never accepted Christ into their lives, for whatever reason—perhaps they already had a religion useful to them. What Dante was driving at was likely the ineffable mind of God and being not only connected to it but a complete part of it, meaning not separate. This last part, heavily implying the loss of individualism—much like Arthur C. Clarke’s concept of a “group mind” in the novel Childhood’s End—is an almost unimaginable thought to many people and likely very unpleasant in many ways (How would privacy exist in this world? Well, it would not.) but this concept of eternal pleasantness is strikingly similar to the trajectory that Dom and Mal were taking in their dreamworld. Although they were not “united” with God per se they were with each other in the same fantasy for their eternity, which in turn is likely what probably drove Mr. DiCaprio’s character mad. He deduced that, in fact, perpetual bliss can become quite dull, even painful without a little danger, a bit of randomness with mortality perhaps. So being separate, whole, and stand alone, might have been the point Mr. Nolan, (Or whomever: pick your author.), was trying to make when Dom wanted to finally get out with some sort of “real” life intact. But does he? That answer, of course, was none clear which brings me to another point.

Remember Dom’s uncanny parallel in the last scene to his wife’s subconsciously manifested and supposed avatar (that’s more than a mouthful), who explicates that he truly can see his kids whenever he wants? Well, that was eerily reminiscent of the ending for a film called Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky, a Russian director during the Soviet era of his respective country. In Solaris psychologist turned Cosmonaut Kris Kelvin must venture to a deep-space station and diagnose the welfare of its indeterminate crew who have gone all but incommunicado. The planet that the station orbits turns out to be the perpetrator of all the hallucinations and confusion, read: manifestations, and Kelvin is revealed also to be victim of its apparent strange machinations as well. But nowhere is it ever spelled out, however, the planet is attempting to destroy them, rather, it seems to be attempting some sort of indecipherable communication.

Eventually the inhabitants become spellbound by the planet’s dream like power and Kelvin decides to accept its weird seductiveness and go in (Sound familiar?); seemingly forever. This decision is very close in tone to the one Dom makes at the final seconds of Inception: instead of neurotically obsessing over his wife’s top one last time he does not even push it aside but, even more subtly, simply ignores it then fauns in the unimaginable splendor of that fleeting moment. A moment that haunts both men throughout their adult lives. By the end of the film Kelvin appears where he started: his childhood home in a rural retreat with his father manifesting himself after a recent report of death. This scene, with its ‘thin air’ composites of both home and family, eerily parallels the last scene with Dom reuniting with his children, of which he cannot decide are real or not, but resolves to not care either way and just accept this “reality.”

But what might actually be more interesting to contemplate than that infamous black-cut screen (Wait for that one later.) is deciding what emotional development both characters arrived at: is Dom complicit in his circumstances, which seem overarching and infinite like the Escher staircase? Is Dr. Kelvin just ignorant of Solaris and the power it has over the conscious mind? Or are they, as Mr. Nolan alluded to in interviews, actually remnants of the final chapter in a cathartic journey and simply accepting of the things that be, the shape their lives have taken? With or without their loves but at peace with whatever they do have? Maybe this is a more mature perspective to take in life, especially in light of such insurmountable odds, and maybe this is what both directors were proposing. But who would honestly know for certain as that is a choice we are likely presented towards the natural end of our personal journeys? While something also of interest within Solaris, in terms of just plain weird luck, is the last shot when the lens pulls back to reveal the roof missing, and a shower of inexplicable water being poured down from nothing into the house and on their heads. A picture both bizarre and beautiful at the same time. Notice something even more strange? The house—it stands eerily reminiscent of the same wood paneled home that Dom and Mal bought and remained for forty years in their imagined prisons. Unsettling indeed. A coincidence? It could go either way.

The manifestations of Solaris are also similar in theme to the “projections” of Mr. Nolan’s film, where the subconscious almost betrays the characters’ true feelings (in this case Dom’s) and subverts them into obstacles the protagonist must deal with and thereby refocus the destination of the plot. Even the wife of Mr. DiCaprio’s character is strangely reminiscent of Dr. Kelvin’s from Solaris, the embodiment of Freud and Jung, she comes from the deepest echoes of memory and emotion: an eerie composite folded from the guilt of a man’s mind. Both are not “real” in any corporeal or even ethereal sense, but truly an amalgam of thoughts and feelings extant from the main character’s mind. They are almost a physical metaphor of the negative thought cycle in depression: how one guilty thought leads to another, creating a chain a person can only break through self forgiveness. This is also a place where Blade Runner ties in: with the appearance of nearly perfect human clones—both in comparison and physical attractiveness—writer Phillip K. Dick and director Ridley Scott were presenting the historically mused question of what is real? What we make or what we already know? Sometimes we try to remake what we know which usually relies on the projection of the mind’s eye, a tool very duplicitous and faulty. But our productions, through memory or art, sometimes come out very lifelike and we wonder where the past ends and our cloudy emotions begin. Mal is a “woman” fraught with a man’s interpretation of a woman but obviously not really whole. There is something missing in her “imperfections” as Dom states: an intangible flaw he is ever seeking as a man because that seems more real, and as a result is more ideal than perfection itself. It is that strange and ineffable difference that separates a true conversation with a lover from one remembered: the one which loses its romantic ring after a few playbacks.

I was also reminded of a French film very dear to me as well, called La Jetée. Although to call it a film is sort of a weird mislabeling as the production possesses no image progression in the traditional sense of movies, but actually uses a series of still photographs. As a sequence of photographs takes place in a location the voiceover offers the audience cues, setting a platform to create the motion in the mind as one might interpret a story in collection of photos from a friend. If you are not familiar with it La Jetée was the inspiration for the Terry Gilliam Sci Fi thriller Twelve Monkeys, although that one takes many liberties with the original plot. In it a man in the near future is chosen after the world undergoes an unnamed apocalypse to participate in an experiment involving time-travel in an attempt to undo such a dark fate to the Earth. He falls in love with a woman from the past, a seemingly star-crossed affair that is never quite requited. Possessed by her image he forever seeks the woman out despite having to forge on through the drudgery of his impossible journey, hoping to one day reunite with his lovely. This basic and visceral thread is very similar to the emotional lure that Mr. DiCaprio’s character is motivated by; sort of a selfish but understandable obsession with what once was.

But then, of course, there is the implied epilogue. If you have seen this one, do you remember the final scene in Pan’s Labyrinth? Because there are only so many feasible possibilities about the nature of afterlife, or its nonexistence, this also is a clue into the nature of dreams and death in all film. We are presented with another world which, up to this point, was only referred to in dialogue by that shuttering faun in Ofelia’s room. Here is a place of reverie and regalement, of peace and romance, in the sense of a child’s interpretation, but is not all sense of peace childlike? And so innocence becomes a major string we sense in all these films, while solace and release are truly innocent qualities. Implicitly, Labyrinth has us decide what fate Ofelia really had in the epilogue: was she asleep, dying, or was she really transported to another, more beautiful kingdom? Spain is known for being a place of almost magical history with long tales of knights and kings and that almost in itself ensures the subject of having fantastic exploits, but somehow for our modern cynicism that just does not taste right. We have to rationalize things as an audience these days, and maybe that is what directors and critics have been doing (Bride of Frankenstein had some heavy undertones about homosexual marriage, and when did that come out?) since day one. So maybe Ofelia did not reach the splendid after-kingdom, but perhaps what Mr. Del Toro and Nolan were trying to say is that their characters found forgiveness for themselves, and more importantly, dignity—a sense of pride in their actions despite what others might have thought of them. So this cycle of negative feedback like with the projections and clones is what leads to the eventual resolution, usually death—or afterlife, and some measure of catharsis. Further, with the inclusion of both protagonists’ family and home during the endings, we are showed the release of suffering which, I gather, was what Mr. Tarkovsky and Nolan intended to argue was most important; although with Ofelia it would seem the faun and the other magical beings were the creatures closest to her, taking the place of the other characters' families.

Another Science Fiction classic in a similar vein, often thought to be of great influence on Solaris, is the now canonized 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by the Bronx auteur himself Stanley Kubrick. Another film by this director would also have some strange wardrobe influences on the other epic by Mr. Nolan, The Dark Knight: Mr. Kubrick’s thief in The Killing wears a mask uncannily similar to those worn by the bank robbers in the more recent film. Back to the original comparison, however, as Keir Dullea’s Dr. Bowman exits the celestial tunnel that consumes his ship, and much of his sanity, he finds himself of all places inside a well ordained, floor-lit master bedroom. As time begins to fade by in a zoetrope like motion sickness we see David Bowman see himself aging at a seemingly accelerated rate which leaves us (And him.) wondering what exactly is happening to him, where he is at, and most of all, if any of this is real. Dom’s predicament is quite similar in tone, although not so much in exposition, as to what Mr. Dullea’s lost astronaut might be feeling. A sense of “what is happening to me” or “where am I” is felt at the ultimate point in 2001 but actually seems to trouble Mr. DiCaprio’s character, and us, throughout Inception. In essence, although the spaces 2001’s protagonist dwells in the final moments appear more real, they still seem very manufactured, albeit by a higher intelligence. It is only going beyond the film we learn the true intention of the bedroom as a “gift”—by the aliens who constructed the monoliths—for Dr. Bowman to dwell in his final days before becoming the star child we witness in the final shot. Any such clarification, and revelation, in the newer film has yet to be divulged; although, do not give up hope, given that Mr. Nolan has plans to release a video game, of all things, some day as a side story.

Perhaps one of the most prevalent films to arouse my attention in similarity was, of all films, not speculative fiction nor fantasy but a gripping and violent elegy in the deepest intonations of urban realism. Taxi Driver, strange as it may seem (Or not.), had some very surreal and stylistic signatures which could only be garnered from the French call to arms of auteur filmmaking, embraced by the young artists of the New Hollywood class; in this case Martin Scorsese. The final shot of Robert Deniro’s Travis driving off with Sibyl Shepherd, his undying amour realized, to peaceful music and quiet streets is a weird counterpoint to the mayhem and violence (Which was brash even for this director.), presenting a very offsetting and enigmatic edge to it. One could not help but feel like some footage got lost in the editing room and leftovers from another production were tacked on. ‘How dare Scorsese leave us with an unearned happy ending?’ How indeed? But there was perhaps a more sinister intention at work here. Maybe the ending was not meant to be taken literally—perchance were we as the audience supposed to be conflicted? It has been proposed by many critics that this last reel was more a hallucination, or a bit more comfortingly, a vision by Travis in his final moments before certain oblivion.

Such an argument would really make sense in the context of an unforgiving and isolated, but heavily populated, urban sprawl. And this parallels how Mr. Nolan said in an interview “the point is he made peace with himself” or something to that effect, in his grand vision. For me it seems to weigh more heavily on the “he’s still dreaming” argument as Dom’s whole life seems to be a hall of mirrors with no end in sight, and escaping that reality almost feels like a disservice to the overall tone of tragedy and despair of Inception. Some might argue that he did indeed make peace with himself: and that is what is important. But inside of what? And where? I do not know if that is enough to actually make me feel happy about Dom Cobb's ultimate destination, but it is definitely a good enough potion to keep me intrigued. Then there is that other surrealist moment strait out of the playbook of An Andalusian Dog—Travis making a phone call to a mystery receiver (His parents, maybe?) only to have the camera leave its subject behind (When did this ever happen before in the history cinema?) and dolly down an apparently empty hallway. The emotion it evokes is shuttering…and shivering, I felt it kind of had a similar element to the penultimate sequence of Inception where Dom takes his dead-man’s walk down to customs. Both had a weird ghost like hovering into unknown territory, although the latter with seemingly more innocent undertones for its endgame.

But what about that horrible black cut? What the hell did that ever mean? Well, it is strange but explaining the black screen is actually easier than explaining what happened after it. The most glaring example of a similar filmic sequence, the one I think was in a lot of people’s minds, is the ending to the Sopranos. What a weird and anticlimactic letdown you say: but perhaps in hindsight that really was not as underwhelming as the strange and esoteric ending of Lost, which of course, lost me (ahem). Anyway. I was never a big fan of the show but I know for a lot of fans that not getting a dutiful payoff to the series you invest years of loyalty to can really sap your sense of wonder and devotion. I have been told that somewhere in that infamous last scene in the diner the camera takes a first person perspective of Tony while he’s talking, maybe not when the actual screen goes black, but at least sometime during that period. This actually makes a lot of sense and sort of redeems David Chase’s choice of arbitrary conclusion over the symphonic bloodbaths of almost every Italian gangster drama.

But, then again, how did GoodFellas end? Ray Liotta’s character goes into hiding as an innocuous everyday “Joe”: so maybe Mr. Chase just got a bad rap. Anyway, back to the ending, if there is indeed a point where the camera is first person in Tony’s perspective—meaning through his eyes—then that taken with the infamous jump to black would really lead to the sign that Tony was indeed killed and there is no reason for further theories or discussion. Taken with the first person angle and coupled with the fact he is the protagonist of the show, and the obvious development that there was a hit on him, all lead to the very strong impression that a black cold ending is a metaphor for certain death. Because if it is about Tony, and you are shot to death, what else would come after black? What else could signify the unknown better than that image, or absence altogether? What a perfect metaphor: the only other equivalent in art likely either an empty page at the end of The Big Sleep or a blank canvas hanging at the MOMA. So that, truly, is a fitting end to his story.

But then again what if that was not Mr. Chase’s intention? Not that I am trying for dissonance in my own argument but I believe this is a key that relates to Inception’s ending. What if the black screen meant something else more ambiguous, such as with Mr. Nolan’s film? It is possible to see from another angle that not one ending is true, but that all realities of Tony Soprano’s final destiny are valid? He lives, he survives, he thrives, he reconciles with Carmela, he does not, they stay separate—or—he dies, he goes back into a coma, he gets made finally by the Feds, he is reincarnated as a Lama, so on and so on. So maybe a black screen is the most stark example of art representing death, a forever journey, the last, the big sleep, but perhaps there was something else Mr. Nolan was really trying to say with his film. That the simple fact the top spins, wobbles, is heard to maybe fall but is not shown to, it is possible this is a sign that Cob made it out and did not make it out—oddly enough, that all possibilities are true and we are just playing a weird game of free will. And free will, infinite possibility, our destiny in hand, all seem to be the game the players are all dealing in with this film, hell, in all films and stories. Are we controlled by pretentious and detached Gods high in the sky, or are the Gods really just a motley crew of stage-operators off to the side waiting to give us our cue to fly? That being the case—okay—good job, everybody, but can we stop being Meta for once in our heist movies and crime thrillers and just have an original, legitimate payoff?

But one last example I find strangely fitting was a film called Young at Heart, starring Frank Sinatra as a rambling grifter with the uncanny ability to—yes—play the piano, smoke too many packs of cigarettes while drinking unhealthy amounts of Scotch (How much isn't, right?) and sing. HOW NOVEL, YOU SAY! If you have not seen this film yet—which, considering if you are still reading this you probably have not—I obviously recommend viewing it before you read the next few sentences...done? Okay, let's go: Mr. Sinatra at one point was actually pretty serious about his acting roles, so serious in fact, he made a film not only about the Red Scare (AHH! Zombie sleep agents! But seriously.) but one about detachment, loneliness and self destruction; and it was good. Really good. If not a bit——surreal. It still has that weird triteness that was rampant in star films of the day, but there is something more going on, something seething underneath the performance of ol' Blue Eyes. And although it is a clash to the effects the other players put on, it is not overstated or disingenuous. It is actually well tempered. Indeed, Mr. Sinatra's character is so dark and cynical, he decides to do a good chase of liquor while ice skating his old bomb through a snow storm and off into a ravine—that is correct—Frank Sinatra's character commits suicide even after he gets the unbelievably blonde lead lady. Wowzers. But wait: there's more! Much to our confusion—or perhaps chagrin—HE LIVES? Wha? He lands an antiquated vehicle with safety equipment comparable in technology to the Gilded Age into a precipice—and lives? And that's not even the weirdest part. After being in near death and wrapped head-to-toe in bandages he is revealed to be unscathed. But you saw that one coming, didn't you?

Then we are left with him finally completing a tune that had been escaping him the entire plot line hence, like about rebirth and redemption maybe, bra? Anyway, he sings the tune on piano, right, we see his lovely lady, then we exit out the window to reveal his lovely suburban block that he has been welcomed into. But there's something really off about this street. Especially, considering the main character just attempted suicide, why is everything so damn—perfect? The trees all spherical and what not, the lawn in awesome 90 degree angles, and the bricks all lovely and burnt auburn red. Something strange indeed. So strange, if you do an internet search and look up the making of Young at Heart you just might find that—yes—the ending was fixed. Or rather altered. There was another ending where Sinatra did truly die in the film, and made no sweet undead returns. The actor/singer-musician/womanizer-extraordinaire had just completed several other roles where his lead character kicks the ubiquitous bucket and decided this one time it was in bad taste, chum. Aha, but what is it? I suppose it depends on your point of view. He thought his character deserved a reward for his redemption, but the surprise survival of his character—in good and handsome health no less—is so jarring, so disparaging and perplexing, you can't help but feel a bit cheated in a way. And this feeling, one I can only describe as a detached and omnipresent unnaturalness, my friends, is a perspective I truly wonder if Mr. Nolan might have contemplated with his story's title character.